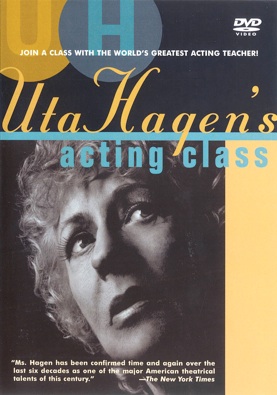

Uta Hagen-The Best-The Legend

Uta Hagen

Actress, Teacher, Writer...Legend

Because she has had a long, distinguished career on the stage, and because for decades she has been one of the most important acting teachers in America, and because she has written with wit and clarity about the technical craft of acting, Uta Hagen has had a profound influence on the way acting is practiced, taught, and thought about in this country.

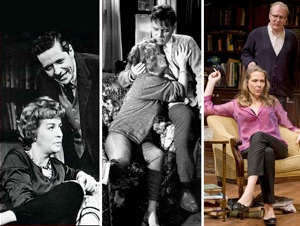

Uta Hagen made her professional debut in 1937 at the age of eighteen as Ophelia in an Eva Le Galliene Hamlet in Dennis, Massachusetts. In 1938 she made her Broadway debut as Nina in the Lunts production of The Sea Gull. She played in twenty-two Broadway productions, including the legendary Othello with Paul Robeson and Jose Ferrer.

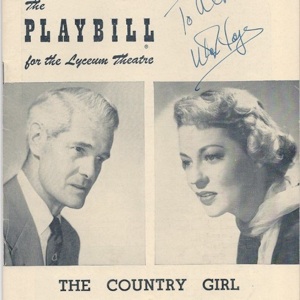

In 1948 she re-invented Blanche DuBois for the national tour of A Streetcar Named Desire with Anthony Quinn, and then succeeded Jessica Tandy's radically different Blanche for the Broadway run the next year. In 1950 she won her first Tony award, the Drama Critics Award, and the Donaldson Award for her creation of Georgie Elgin in Clifford Odets The Country Girl. She starred in such classics as Shaw's St. Joan and Turgenev's A Month in the Country, and in 1962 she created Martha in Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, winning her second Tony and second Drama Critics Award, as well as the London Critics Award. She has also appeared in many TV specials and several films.

Since 1947 Hagen has taught acting at the Herbert Berghof Studio. Together with her late husband, she trained generations of actors: Geraldine Page, Jason Robards, and Matthew Broderick are among the countless others who reached prominence.

As Jack Lemmon wrote, This extraordinary woman is one of the greatest actresses I have seen in my lifetime, yet she has deliberately made her acting career secondary to teaching and directing others so that they might benefit. Lord knows what exalted position she might have attained had she chosen to concentrate on her own acting career, but I guarantee that she has absolutely no regrets. Nor should she, because she has given so much to so many.

Her books, Respect for Acting (1973) and A Challenge for the Actor (1991) grew out of decades of collaboration and exploration of the actor's craft.

In addition to honorary doctorates from Smith College, DePaul University and Wooster College, in 1981 she was inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame, in 1983 into the Wisconsin Theatre Hall of Fame, and in July 1986, she received the Mayor's Liberty Medal in New York City. In 1987 she was given the John Houseman Award and the Campostella Award for distinguished service.

Since her husband's death three years ago, Hagen has taken over the chairmanship of HB Studio and the theatre of the HB Playwrights Foundation. She honors his memory by continuing to shape their school as a source of inspired teaching and practice for theatre artists.

Uta Hagen has brought beauty, drama and dreams to the world, leaving her extraordinary legacy every step of the way.

[ WIC Main Page | Biographies | Words of Wisdom | Newsletter | Birthdates | Living Legacy Awards ]

Uta Hagen-The biggest Influence ever!

Uta Hagen, 1919-2004

Respect for a master actor and teacher who inspired others through the unmatched sublimity of her example

published: January 20, 2004

Onstage or off, everything Uta Hagen did was complete. She came into the theater as a teenager, playing Ophelia to Eva Le Gallienne's Hamlet, and stayed for the remainder of her long life, acting, teaching, running a school and a theater, and writing books on acting that have become part of its permanent vocabulary. She carried on the theater's great tradition, devoting her life to it, demanding and giving only its best. She played new plays, American or German, measuring them by the greatness of the opportunities they offered her and testing them against the great plays that had nourished her: Shakespeare, Shaw, Chekhov, Turgenev, Brecht. Movies and television, by which foolish people think to evaluate acting, were only an incidental caprice to her, and her performances will be remembered when most such things have become industrial detritus.

I first saw Uta as Martha in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The impression she left was so strong that years later, when the prospect of meeting her arose, I was terrified: Martha had existed for me so completely—I still remember the angle of her body in the doorway at the top of the show—that I assumed I was going to meet Martha. I was startled to find, instead, a quite different person with only hints of Martha. I found this to be true, subsequently, in every other role I saw her play: Each was a completely different person, a not-Uta who had some traits in common with Uta, but lived a complete and separate existence of her own.

Uta lived so completely in the present that, in the few brief times I spent with her, it never occurred to me to ask her about her illustrious past. Like her roles, it seemed to belong to another person. My rational mind thought of asking her about that Ophelia, or about her Nina to the Trigorin and Arkadina of Lunt and Fontanne, but it would have seemed absurd to inquire about these things; her vitality always made her seem decades younger than her calendar age, obviously too young to have been in that ancient past; a different Uta must have done all that.

Writing about Uta's acting was and remains an impossible task. The sense of life she conveyed was so full, so complete and seamless, that one could never find a point from which to dissect it. She made everything she did onstage remarkable and individual, because it was part of the life of the character, yet she never did anything in a self-conscious way that could make you feel she had been directed to do it or was drawing your attention to it. It was simply what the person she played would do, brought to an intensity that made the most banal motions riveting. I would find myself explaining enthusiastically to people how important it was to watch Uta take off her coat, or tear up envelopes, or pour a cup of tea, and then, hearing myself, break off, feeling like an idiot at my inability to recapture the unrecapturable and explain the sublime.

Most remarkably, this sublimity came, in an almost Zen way, from her complete matter-of-factness. I have seen few artists so magical onstage; I have never met anyone so completely down to earth. I first met her when I staged a workshop of a small musical revue at HB Playwrights, involving one of her infinity of devoted students, the late Martha Schlamme. It seemed normal to me—because Uta made it seem normal—to come in to rehearse and find Uta cheerfully sweeping the stage to get it ready for us. ("Oh, please let me do that," I said. "It's my theater," she answered.) This, too, made it hard for me to ask about her past, though Uta would no doubt have been perfectly willing to discuss St. Joan or Othello while she swept. When I worked with her, much later, on a reading of a play I had translated from the German, we spent some time going over its dense and repetitive text; she never asked a question that was not completely sensible, and she never rejected any reasonable answer. At the reading itself, after only a few days' rehearsal, she delivered the role with an authority that suggested she had been working on it for months, perhaps years, and knew the life of the character—a life far different from her own—from so deep inside that there was no distance between them.

Michael Feingold

Uta Hagen was a great teacher, a great actress, and a great cook. Also, she was nobody's fool and I both admired her and cared for her deeply.

Edward Albee

"I love to act." That husky voice spoke the words like a lover confessing pleasure. It was primal and pure. Satisfaction connected to raw need. We were walking down Bank Street. It was 1992. I had just seen Uta perform an act from Charlotta, a one-character play about Goethe's mistress, at the HB Playwrights Foundation & Theatre. It's my least favorite kind of play, historical monodrama. But Uta had enthralled me. This irrepressible spontaneity, each moment seemed a discovery for her and for you the audience. Despite my critical predisposition I found myself intimately involved with and deeply moved by the human animal on stage. She was so alive you had no choice. If you looked away from her you were afraid you might get caught.

Nothing was casual about this love. It was the passionate, savage, and all-consuming kind. Love that is born from belief. Belief that the theater is a gift we have given ourselves, to explore, discover, understand, and celebrate the mystery of being alive. And acting, as I came to understand what Uta aspired to onstage, was in T.S. Eliot's words "a condition of complete simplicity (costing not less than everything)." I've never worked with anyone who worked harder, and all the work was about getting to that place. Her extraordinary attention to detail, where everything onstage and off had a specific significance, was her way of achieving freedom. "You have to know everything to be completely free," was the mantra I learned as I watched her work.

Since her stroke in the fall of 2001, Uta had not been well, and for those of us who were with her through those last two years, her death was not a surprise. But even so, we are left with the feeling that this great and by the end somewhat ravaged ship has pulled away from the shore and headed out to sea. In this age of immediate news, instant success, and momentary stardom, how easily we lose touch with the sense that as artists, who we are and what we do is only a small chapter in a much greater history. Uta carried the substance of that history in her soul. She first worked for Eva Le Gallienne and the Lunts, so she is one of the last to come from that time when actors were able to consider a life in the theater to be the highest calling. And she bore that in her bones every time she stepped onstage.

Working with her changed you as an artist because the work was never done. She never said a line the same way twice; it was always in response to what had just been said. And so much of what we watched was the way she listened. She felt fear but her acting was fearless. She wanted to find that magic edge of being so completely in the story that she wouldn't know or be thinking about what happens next. Uta loved long runs. She loved sharing with an audience all that she had become in the course of rehearsing a play and, with their new participation, constantly surprising them.

No one has influenced the quality of acting in this country, and maybe even around the world, the way Uta Hagen has, as an actor, a teacher, and a writer. No other artist has had the talent, passion, and commitment she had for doing all three. So now those simple words, "I love to act," carry the weight of a full life's work. And as we watch that vessel slip out to sea, let us know, let us love as she loved, and most of all, as we work, let us remember.

William Carden

Uta Hagen was my acting teacher for several years when I first moved to New York in the mid '70s. She remained an extraordinary influence and inspiration to me throughout my career. Every role I have ever portrayed on film, TV, or on the stage has Uta's technique all over it. I still look over those copious notes I took in her class; I still reread parts of her books before every job I take. I have such vivid memories of going to her class—lugging my props on the subway down to HB Studios—trying so hard to impress her, to please her. I'll never forget finally getting her ultimate approval—her "no criticism" accompanied by a light-filled joyous smile. When that happened, I left the class on top of the world. No amount of rejection or lack of messages on my answering service could shake the high. Her class was the one true highlight of the whole week during those early days in New York City, struggling as a waitress/agentless actress.

I never missed her performances on stage. She completely practiced what she preached—all that homework, preparation and specific personalization allowed her the full freedom, spontaneity and aliveness that she taught us in her classes. She was my teacher, my mentor, my constant source of inspiration and my friend—I, and so many others, will miss her deeply. She was a force in so many people's lives—the ferocity of her talent that was made even greater by the generosity of her heart.

Christine Lahti

Uta Hagen was a great and defining force in the American theater. She was a remarkable actress and teacher of acting, uncompromising in her beliefs. She was my friend, and I will miss her very much.

Horton Foote

Ms. Hagen had a great capacity to have fun. She rarely went to dinner parties, but once in a while she would break loose. About 10 years ago, on Halloween, I was in New York doing promotion for a television show. They sent a stretch limo and I was riding down Fifth Avenue to pick her up at her home on Washington Square. At 10th Street and Fifth Avenue there was a police block; the barricades were up for the parade. I said, "But this car is for Uta Hagen, my teacher." The next thing I knew, I had a motorcycle escort to Ms. Hagen's apartment. So I called her and said, "Ms. Hagen," (I always called her Ms. Hagen), "lean out the window, there's something coming." We went to her favorite restaurant uptown before the opera. She had several vodkas, I had several bourbon manhattans. At the end of the meal, the man who owns the restaurant said that Ms. Hagen was his guest because the bartender was her pupil, as were the hatcheck girl and several of the waiters and waitresses. They wouldn't let us even leave a tip. So we got back in the car and went to the Metropolitan Opera. At the box office, I was told that the tickets were free, because "we heard from the press agent that Ms. Hagen was to be your guest." We took two acts of Il Trovatore. It wasn't very good. The second act featured a staircase from here to infinity. Everyone had armor on, and Ms. Hagen said to me, "You'd think you'd hear one clink." We went up to the Grand Tier and sat at the bar for two hours because we had to wait for the car. We kept drinking for free because the bartender was one of her pupils. When the car came at 11:15 it was covered in flowers—on the backseat, the floor, the back window. The chauffeur explained that his sister, Kate Mulgrew, had been her student and had learned so much from her. He also wouldn't accept so much as a tip at the end of the night. After stopping off at the Tunnel and Limelight (where again we weren't allowed to pay for anything), we got back to her apartment around 3 a.m. and were sitting in her kitchen having a nightcap. I sat there and looked at this woman and said, "Ms. Hagen, you are the richest woman I know. We went out for 10 hours in New York City and it didn't cost us a penny. Golda Meir, Mother Teresa, and Eleanor Roosevelt would have had trouble doing what you did tonight."

Charles Nelson Reilly

UTA—everyone called her by her first name—was playing Blanche DuBois in Chicago. Once a week, every week, she taught a two-hour acting class for her company and other actors who were playing in the city. I was in Medea with Judith Anderson and wanted to be a part of Uta's workshop. She told me that the class was full but I could audit it. In my datebook for 1949, in capital letters, I find "UTA-1-3" for Tuesdays in November and December.

She was an inspired teacher. Her influence on young actors was as potent as her effect on her audiences during her great theater career. She gave me confidence 20 years later when I began to teach at Juilliard.

Uta—we were all her students. Her generosity of spirit will continue to be an inspiration to all who love acting and the power of theater.

Marian Seldes

Stanislavski wrote a book called An Actor Prepares, which was very nice of him, but nothing could prepare you for acting with Uta Hagen. Ms. Hagen was a serious and dedicated artist with a powerful ability to immerse herself in the moment-to-moment reality of a character. She also stopped me in the middle of our first day of rehearsal and said, "If you say that line that way, I won't get my laugh."

When the director and playwright suggested that the play should be performed without intermission, Ms. Hagen strenuously disagreed, saying that there was a natural break in the middle of the play, that an intermission would give the audience and the characters a needed sense of time passing, and that she had no intention of going an hour and a half without a cigarette.

In our second preview, during a quick change, I heard a terrible crash onstage, followed by a gasp from the audience. I came out to find Uta sprawled on her back on the auditorium floor, a small crowd around her. In the blackout between scenes, she'd missed the stagehands' offstage flashlights, headed for the lights along the auditorium floor, and fallen off the edge of the stage. She was 82, and she hadn't broken a bone. After we got her gently to her feet, she was determined to finish the play, and it was only after a lengthy argument and the intervention of the theater's managing director that she relented and went to the emergency room. Later she confided to me that she was sure that if she'd gone back on she'd have gotten a hand.

Uta was great because she was everything—theatrical and practical, quick-witted and methodical, vulnerable and resilient. We fell in love, she and I, and we consummated our passion eight times a week, twice on Wednesday, twice on Saturday. I know she loved to teach, but she lived to act.

David Hyde Pierce

Anne: Uta was a very important part of our lives; she laid the groundwork and gave us a map for the craft of acting. She was very loyal to her students and we felt privileged to be included among them. We were both in The Good Woman of Setzuan with her, and I was in A Month in the Country, directed by Michael Redgrave. I did summer stock with her, too. It was an adaptation of a Sardou farce. I played the French maid and was also Uta's dresser.

Jerry: If you were good enough to be her student, you were good enough to work with her onstage. She treated you like a fellow player. She had a social conscience, but she didn't preach. You absorbed it through being with her. And it wasn't just in the classroom. It was parties at her home, Christmas holidays. You'd become a part of her life.

Anne: Let me add that Edward Albee was quite right in pointing out what a good cook she was. There was, and I mean this as no disrespect, an earthiness to Uta. She had a lusty, raucous sense of humor. God, she loved a good joke.

Jerry: She was also very motherly to us. A strong mom. If you needed discipline, she let you know it. Once, down at the studio, I was doing a scene that involved a lot of anger. I started beating up the pillow, and feathers started flying all over the place. After the scene, she said to me, "Jerry, you'll clean that up."

Anne: She was always concerned about the struggling actor. She knew how economically difficult the actor's life can be, and even after Herbert died she fought to keep her classes affordable. She never overcharged. Uta possessed a democratic spirit.

Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara

I met Uta in 1986, when Herbert Berghof invited me to do a casual reading of Ibsen's When We Dead Awaken at their home. I had read her books in college and was so honored and excited to meet her. I remember feeling an instant rapport. In 1987, Herbert and Uta asked me to play Uta's daughter in Donna de Matteo's The Silver Fox in East Hampton, and it was there that our mother-daughter connection began. There was something familiar about her. Uta was born in Germany, and my Latvian immigrant parents had lived in Germany for five years in a refugee camp. Uta had spent her younger days in Madison, Wisconsin—I went to college in Eau Claire, just down the road. Uta was a Gemini, as was my biological mother. In 1995, Uta and Billy Carden invited me to play Uta's daughter in Nicholas Wright's Mrs. Klein at the Lucille Lortel. We ran for nine months and then toured for four. The months we played together were the most exhilarating of my life. I had found my artistic mother. She had a striking intelligence and a passionate heart. She demanded much and gave more. She had an unbeatable work ethic. She used to say, "It's not whether we can do this, it's whether we want to do the work." Rehearsal was heaven. Every day she came in with a million ideas about how to make it better. She was unrelenting in her excavation of the play. I remember the final performance of our tour—we were in Chicago. She came offstage after the curtain call speaking of some moment earlier in the play and said, "Now I know how to play that moment!" She was still searching. She was reticent to give notes to her fellow actor, knowing how tricky that can be, but on occasion the amazing teacher inside her would offer something to me and it would inevitably be correct. She had an extraordinarily meticulous process in endowing props with history and detail. She was absolutely spontaneous, fresh, and alive every night and taught me to maintain that over a long run. She taught me how quickly a character can think, and to play the action, not the emotion, in a scene. She taught me to trust my impulses and instincts, and she validated me. I think perhaps this was one of her great gifts. She was tough, she was demanding, she was tenacious, she did not suffer fools, but by God, when she said something positive you felt validated, and more importantly, hopeful that you could grow in your craft and through hard work and passionate focus become a better actor. She was a phenomenal teacher, a grand colleague, and a true partner onstage. She was also so much fun to be with. The company and I spent countless evenings at McBell's talking of the play or listening to Uta's priceless anecdotes from past plays. We would enjoy our sea breezes and "talk shop" or politics and heaven help me if I ordered chamomile tea instead of a proper drink. Uta was incredibly generous. The most thrilling gift came at Christmas when she gave Amy Wright a bracelet and me a brooch, both of which had been given to her by Ms. Le Gallienne, who had worn them onstage when she played in Camille. Uta, in turn, asked us to pass them on to a younger actor when the time came. She was my artistic mother and she filled me with every emotion possible. We had such lovely times together. It was always exciting, it was always demanding, and it was always fantastic!

Laila Robins

I studied with Uta Hagen in the '60s. She taught me how to act. Anything that's wrong with what I do on any occasion is simply because I've forgotten something she taught, and means I must return to her book, Challenge for the Actor, which is the best book about acting I know. Uta, of all the great teachers I know anything about, was the most pragmatic. One day in class, a student said she was in rehearsal for a big Broadway show, and that she was having trouble functioning as Uta had taught her to because the director, a flavor of that month, was demanding instant results upon the receipt of any piece of his direction. This can be risky to the final product of an actor's work, so she was asking Uta, "What should I do?" Uta said, "He wants instant results?" The student said, "Yes." Uta said, "Then give them to him." Uta believed that if you absorbed the core of your technique completely enough, you should be able to make it work for you in any rehearsal situation, and that if you couldn't, well, then that meant you hadn't absorbed it completely enough. I think she thought of her classes as a shelter, a place to work freely and to grow, but not as a place to hide from the insane exigencies of this profession. Anyway, I had studied with her one summer term when all of a sudden she got the part in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? I went to a preview. It was one of the greatest nights I ever had. Not only was it the most astonishing new play I had ever seen in a preview, but it was crystal clear from the opening moment that everything Uta taught could work, brilliantly. And that was true with everything I saw her do in all the years after that, right up to Mrs. Klein and Collected Stories. Her work never settled, in any sense of that word. Her sensibility was endlessly curious, endlessly open to artistic experience. Maybe the reason is contained in an answer she gave to a student one day, who said he didn't understand why she didn't think his scene had worked, because he'd never felt so relaxed. Uta replied, "They don't come to see you relaxed; they come to see you in danger." And she taught us all how to be in danger. I will miss her terribly.

Austin Pendleton

I held her frail hand in mine and, George to her Martha, with more than a little stagecraft, slapped it hard. She loved it. At the full-house, black-tie reading, she chewed the script, the table, the stage—we had no scenery. At 80, she inspired and gave new life to a jaundiced actor. Me. I knew her but for a few weeks. She stays in my mind. We shall not see her like again.

Jonathan Pryce

I remember the exhilaration the first time Uta Hagen said to me "I have no criticism." All of us in her class at HB Studio longed to hear those words. We all knew we were learning from a living legend, and these words meant that for a brief moment, our work had met her expectations. I heard them twice in 13 years.

I moved to NYC to study with her at 19, just a year before Herbert Berghof died. In a city that could eat you alive, he and Uta created a safe house for actors with talent and commitment. If you didn't have the talent, you couldn't get in; without the commitment, you couldn't stay.

Uta Hagen imparted her wisdom for $7 a class. For the price of a movie ticket, I got to study with a master. It wasn't until 12 years later, at the pleadings of her HB staff, that she reluctantly raised the price to $10.

Before my first Broadway show I asked her how to handle my terrible nerves. All she said was "Tits up, Katie." A little shocked by her choice of words, I knew exactly what she meant. Do the work, then free yourself. Over a decade later I was able to return this phrase of encouragement when she was relearning to walk after her first stroke. I would shout it, and she would laugh.

She was my mentor and my friend. "Tits up, Uta."

Katie Finneran

Uta Hagen was one of our country's finest actresses. I first saw her Desdemona in Othello and kept up with her performances on stage and screen whenever possible. When I saw Mrs. Klein in 1995, I dropped her a note to say that in my mind she ranked with Laurette Taylor in The Glass Menagerie. She followed that up with a stunning performance in Collected Stories.

In honor of her 80th birthday and in support of the HB Studios, she recreated the role of Martha from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in a rehearsed reading. She hadn't aged.

Come to think of it, she could have qualified for a National Medal of Humanities, as she is co-creator of HB studios and is a master teacher. She is author of two of our finest textbooks on acting, which serve as benchmarks of university training in this country.

I am proud to say she was my friend.

Hal Prince

You can learn an awful lot from watching great actors work—you learn what good acting looks like and when you work with them they can sometimes tell you how they do it—but they are seldom teachers as such. They do not teach you how you should do it. Uta was the exception. A great actor who was also a very great teacher.

By the time I first met her, I was only 26 but I had done over 60 plays in Canada and England, and I had worked with some great directors—Peter Brook and Tyrone Guthrie; great actors—John Gielgud, Peggy Ashcroft, Alec Guinness; great stars—Katharine Hepburn, Tyrone Power; and remarkable contemporaries—Christopher Plummer, Nancy Marchand, Sada Thompson, Ellis Rabb, Bill Ball, and so on, and had picked up tips and tricks from all of them. I was a confident, experienced, and facile actor and I knew a lot about other people's acting but very little about my own. Until I worked with Uta.

Though I have never taken an actual acting class with her, I have read her books, of course, I appeared in three plays and a public reading with her and had many talks tète-à-tète over the years, and during the course of all this she taught me how to act.

I met her when I played in A Month in the Country with her on television, and she took me under her wing. We rehearsed the play for a couple of weeks and got into the studio and did the camera rehearsals but at the dress run—this was in the days when tape was difficult to edit and you had to do whole scenes in one take—when we got to my big scene, Uta kept stopping and fussing and generally wouldn't let us get a run at it. I was very worried by this but she said "The scene is ready and will be fine but I know you; if I let you run this now, when it comes time to do the one that matters you won't throw yourself at the scene—you will try to repeat the effect of the dress run." This was of course true and I saw that it was true and I started from that moment to learn how to do it—as she does it—always the same but new each time.

A couple of years later, for the English production of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? I came from London to rehearse with Uta and Arthur Hill, who had been playing it on Broadway for a year. I learned the lines on my own and learned the blocking with a stage manager before I rehearsed with the rest of the cast. In the first break of that rehearsal she took me aside and said "You are clipping cues. That means you are not allowing yourself to hear the other actors. You act listening but you don't hear. You are not affected by the other characters. Naturally—that's how you had to learn it. But you must now quickly relearn it to put in the blanks when you don't know what will happen next." Well, it was an unusual circumstance but I'm afraid that was how I always learned lines. I wanted it to be smooth and easy. But she taught me that "the line through" is not a straight line but a zigzag. She encouraged me to delight in playing the glitches—the lies—the secrets in the text and to use the energy produced by acting surprise to vitalize the performance.

When I was trying to become an acting teacher myself I called her a lot for advice, of course, and what her advice boiled down to was "Really the hardest thing we have to learn—and that cannot be taught—is how to want to do it 8 times a week, in sickness and in health, to good houses or bad, free and fresh and the same every time." Now, it is true that you cannot teach that passion to someone who doesn't have it but many of us do have it at the beginning and lose it; and what can be taught, and what she does teach, is how to keep it and strengthen it. She taught me to do it as she has taught many others. I think of it as Respect for Acting. I know she came to dislike that first title of her book but for me it exactly describes her greatness both as a teacher and as an actor.

Richard Easton (from a speech originally given at the the Dramatist Guild Mage Evans and Sydney Kingsley Awards, June 6, 2002)

Oh my Uta, my mighty mentor, ferocious shatterer of illusions, bringer of light. How can I believe you are gone?

I stood at Uta's bed two weeks ago, stroking her arm, blessing her. How could this frail woman be the giant who had inhabited my life?

I studied with Uta Hagen for seven years in my early days as an actress in New York. Every week I climbed the stairs to her small studio on Bank Street. She sat, always at a little table to the right, with a pad of clean paper, a pencil and her cigarettes, armed and ready for work. And it was serious work. God help you if her hand began to write while you were up on stage. I can still hear that pencil scratching in the dark, my heart sinking at the sound. What had I done? What had I left undone? What, oh what would she say? For Uta treated us like pros, even as beginners, and there was no escape from her eagle eye. The lights would come up, she'd lean forward and ask in her deep, scratchy voice full of intelligence and wit and experience, "O.K., how did you feel?" She always asked this question, because above all she wanted us to be accurate about ourselves. She knew very well that one day she would not be there, that we would have to learn how to distinguish good performances from bad.

Uta set standards and held us to them. On the first day of class she would announce, "Ladies, get your hair out of your face now, and keep it there." She paid attention to details: "Don't close your fan after you say the line—it's pointless and cheap. Close it on the line. Good! Now you're someone to be reckoned with; you're strong and clear."

To keep us honest she told cautionary stories of her own youth on stage. When she played Nora in A Doll's House, she learned that if she tossed her head as she made her final exit, she would get applause. Then one night she found the courage not to call attention to herself as she went through the door. There was a heavy silence, the sound of every soul in the house resonating with compassion for Nora. The actress had disappeared.

No matter how many years we spent with her, growing up as artists under her care, she was always the master. Only once did I make the mistake of treating her like a colleague. I confided in her, pro to pro, "Uta, you know that scene in the second act of Vanya, where Elena comes into the room where Sonya has been with Astrov? God, is that a tough entrance—you walk onstage and say 'The storm is over.' You're just standing there, and you have to say, 'The storm is over.' Oh my God, Uta, how on earth do you deliver a line like that?" She looked at me, stunned, her hand went to her heart, her head tilted back and she inhaled a gasp. "How do you deliver a line like that?" she rasped. "Oh, my dear," she began, her eyes searching the space in front of her, "you know what it's like in a big, old summer house, when the skies crack open and the rain comes crashing down, and everyone races to shut the windows, and everything is wet: the floors, the curtains; the bedclothes are soaked; the rain is everywhere. As the storm plays out the house becomes an oven: airless and steamy, oppressive. Your marriage is stifling you; the house is stifling you. You can't sleep, you wander through the halls, and suddenly—suddenly—you are in the room where Astrov has been! He has been there only a moment before! You touch what he has touched, you hold his napkin to your face. It's still warm! He is so near you can't breathe! You could faint! How wonderful! Open the window, get some air! The storm is over!"

Uta held nothing back, not her criticism nor her care. Her comments could be searingingly blunt, but like Ariadne, she could lead you steadily out of the maze. There was only one, ultimate goal: the baring of the human heart. One afternoon I was doing a monologue in her class. I was determined not to hear her pencil scribbling, so my concentration was focused. I relaxed, and became very simple and open. At the end of the speech, she was quiet. Then she said to me, "Lindsay, what you just showed us, that is your power. If you don't know it, there is nothing I can teach you. Do you understand?" I nodded to her and sat down. From that moment I had my mission in life: to share as if there is nothing to fear.

In October, I went to see her. She was bedridden and paralyzed. We talked for a while about the theater, and then she turned to me. "I am frightened," she said. "I am frightened all the time." I held her gaze. "Oh, Uta," I said, "You have nothing to fear. You have done nothing but good. But the fact that you told me. That is your power. If you don't know that . . ." And she began to smile.

Lindsay Crouse

In the summer of 1997 Billy Carden called to tell me that Uta Hagen was looking for a play. I told him that if I did have a play that might be suitable for her, it was Collected Stories, which had just ended its run at the Manhattan Theatre Club. He suggested that I send it anyway, which I did, expecting to hear not another word about it.

A few days later he called again to inform me that Uta had not only read the play, but loved it and wanted to do it. I was perplexed. Hadn't Billy explained that the play had literally just been produced (the estimable Maria Tucci had done it), that the part actually called for a woman closer to 55 than to 80 and, moreover, hadn't he disclosed that the Times hated it? Yes, but apparently Uta was undaunted. In Ruth Steiner, the complex writer and teacher at the center of the play, Uta Hagen saw a role she could sink her legendary teeth into. I thought if nothing else came of it, I would at least have the unexpected pleasure of seeing a theatrical eminence at work—in one of my plays.

Billy rehearsed Uta and Lorca Simons in the two-hander at HB Studio. I stopped by one afternoon and tried to make myself unobtrusive at the the back of the theater.

I had never seen Uta Hagen in the flesh before. Her Desdemona, her Saint Joan, her Martha were performances that took on mythic properties when described by those who had seen them to those who had not. I knew Uta Hagen solely by illustrious reputation and from juicy movie cameos in The Boys From Brazil and Reversal of Fortune.

I watched her play and re-play a confounding piece of business that she insisted on getting just right, seeming more like a working actress than a diva. When we finally met, during a break, she expressed great woe at not looking her best. "I'm meeting the writer and I'm not wearing any lipstick!" I tried to assure her that she looked just fine but she excused herself anyway. When the actress returned wearing fresh lipstick, smoking a cigarette and carrying her dog, she had transformed herself into Uta Hagen. And, later, over drinks, she did something even more remarkable: she became 25 years younger.

Donald Margulies

Is it heretical to say that Uta Hagen was a better teacher than actor? Of course the reckoning is my own, calculated as I test the weight of personal experience and taste. Who could deny that her acting career was beyond distinguished: historic in our theater and culture. But I always admired her performances more than I was moved by them. She seemed somehow out of both place and time, with the possible overwhelming exception of the thoroughly modern Martha, whom I missed onstage but not on record. That vinyl memento does not change my mind, however. Despite childhood transplantation from Germany to this country, to me she remained a grand Middle-European lady of the stage, more from the orbit of Max Reinhardt than the Yankee Stanislavskians. Not really an ensemble actor, she was a star of her craft who, as the great designer Boris Aronson approvingly observed, always knew where the light was.

She was my teacher in the late '60s. My time with her was brief and I was only briefly an actor. But what she gave transformed me. Her classes were different. She would kick you out, for one thing: if she thought you were lazy, if you weren't the artist material she'd taken you for, or if you'd just been there too long. There was not the place for the amateur-actor-professional-class-taker or the housewife with time on her hands—the population that makes "scene study" a New York cottage industry. The craft she taught with such discipline and insight could be taken directly from class on to the stage. The art she taught came from a life-long involvement with all the arts: painting (her father was an art historian), music (her mother, a singer), literature (consider the material she chose), and the rest. She transformed for us the word respect. She presented it to us like a gift. She made it into a clarion call. Respect for acting, indeed, but for all the arts as well, and for all the artists.

Uta in the Village: We lived near one another across Washington Square, though our personal contact ended when I left her class (for the late unlamented American Shakespeare Festival—"You'll get bad habits," she warned). We liked the same restaurant, though: the late very lamented McBell's on Sixth Avenue—wood and brick in dim light, great hamburgers. She dined there regularly with friends and family, always including an avid audience of poodles: Like any other true Villager, absolutely at home with being a bit out of place and time.

James Leverett

Monday, September 5, 2011

Walking and Talking--by Uta Hagen (How to address and solve wandering on stage)

Walking and Talking, by Uta Hagen

"On occasion, I’m certain you have found yourself sitting comfortably in a scene, relaxing into the cushions of the sofa…you were occupied and involved with another character in the play, unaware of your body in any sense except that you believed you were there. Then you rose and stood for awhile as the conversation continued.

Suddenly, the very act of standing became awkward. You became aware of your hands, your legs and feet tensed up, you lost a sense of character and place—and you became an exposed actor onstage, not a human being in a room. Then you protected yourself, attempting to regain composure by assuming a stance—a stage pose.

You had no inner justification or reason for the rise. However, of the rise from the sofa had been connected with the need in the given circumstances (let us say that you rise to get a drink for your friend, to make him feel welcome—then you would have an involving and simple task.) THE REASON FOR WALKING IS DESTINATION. There is a way to avoid mechanical, tense and general stage wandering.

In life, each moment of true wandering has destination, is focused on a relevant object that we deal with on order to further our objective. Suppose you are at home alone, and waiting for a telephone call or a visit from a friend bringing news of a job. You may be impelled to walk to the window to see if he’s in sight, and then you may cross to the telephone and consider calling him. You may reject the idea and take it out on the phone and give it a little push. You cross to the liquor cabinet and actually pick up a glass which you then quickly replace because you don’t want to drink the alcohol so early in the day. The expected friend has commented about your untidiness, so you cross to the chair and clean a grease spot or crumbs in the upholstery. You cross to a wall mirror and check your hair. Meanwhile your mind races from one inner object to the other—those that are directly connected with your friend, the possibilities of the job, what might stand in its way.

In life, your wanderings may seem to lead you to irrelevant objects. On stage, where every second counts, the objects should be selected and dealt with to reveal something new about the character or the circumstances, or both. The objects you contact must be substantiated by the logic of the play.

Of course, the total animation of the body is brought about by a correct incorporation of surrounding circumstances, weather, time, character needs, relationship to the people and things that surround me, and my immediate needs."